It is not a surprise that so many Big Tech CEOs grew up in India

Jaspreet Bindra

The bus to my Cambridge college arrived right on time, stopped precisely at the bus stop, lowered its footboards for people to disembark, and we all boarded it in a single file after every passenger had stepped out. This reminded me of what Vinod Dham, father of Intel’s Pentium chip, told writer Chidananda Rajghatta: “In India, a public transport bus never stops at a bus stop. It is always full, and therefore the driver stops many yards before or after the stop only to disgorge passengers already overflowing. So, to get on the bus, you are attuned to dash 50 metres on either side and get perhaps a toehold on the footboard of the bus. Then you come to America, and what do you see? Bus comes on time, it is almost empty, the driver even lowers the footboard for you to get in. Life is a piece of cake. India prepares you to succeed.” (bit.ly/3VjqUE6)

This to me best explains why many companies, especially in tech, are led by Indian CEOs. The broader metaphor of Indian traffic, perhaps the most chaotic in the world, explains this phenomenon even better. The traffic in India teaches you to follow rules but work around them when faced with obstacles (say, an ambling buffalo). It teaches you to account for unpredictable occurrences all the time and always have an alternate way to get to your destination. It teaches you to multi-task, rather than work sequentially. The traffic makes you humble and accepting of the vehicular diversity on the road—cars, two- and three-wheelers, handcarts, bicycles, bullock carts, and even the occasional ‘black swan’ elephant.

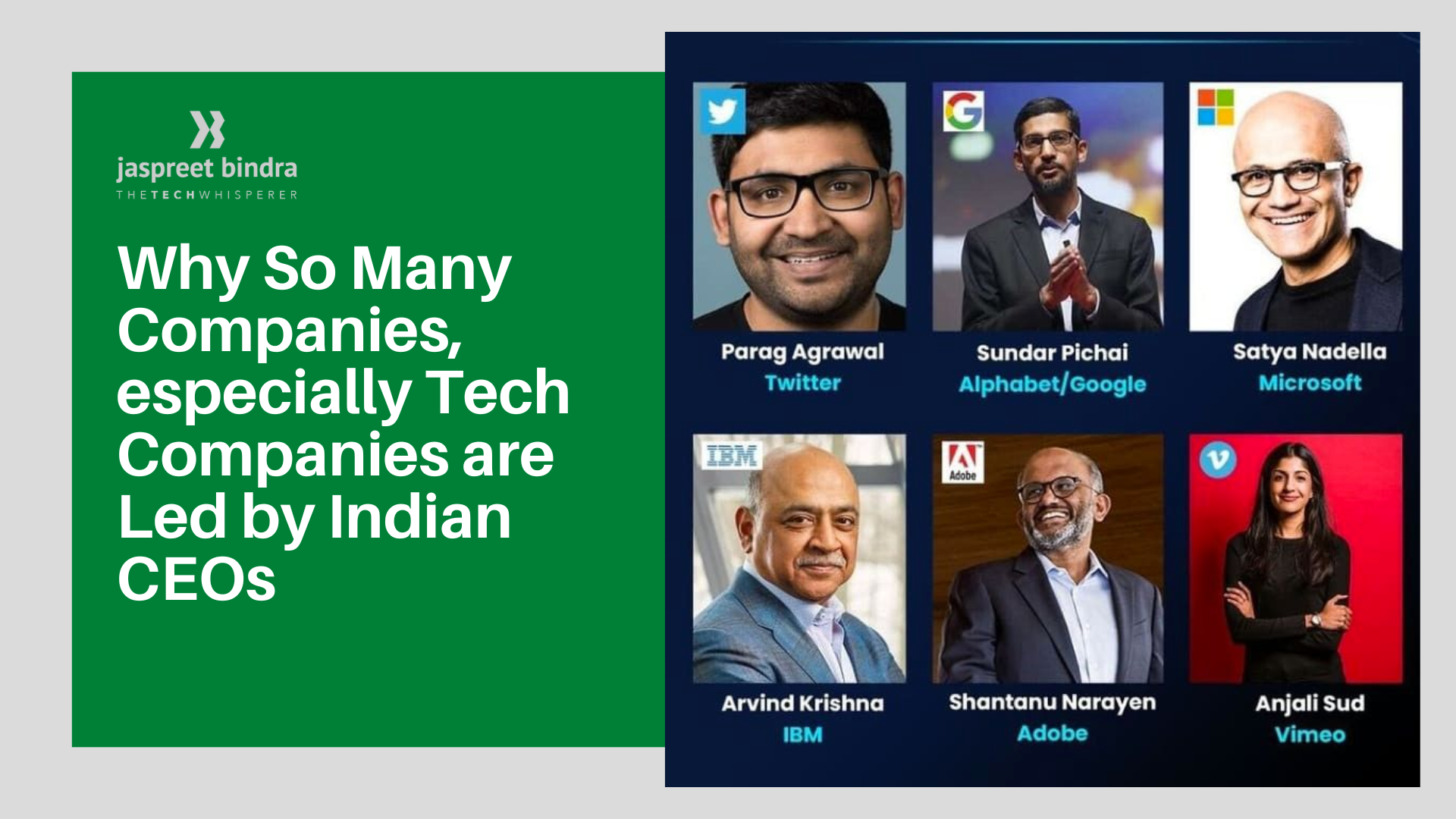

Thus, I was not surprised when I found out that most immigrant chief executives in the US are of Indian descent, with tech dominating the list. While they could be citizens of anywhere, most are first generation Indians who grew up with the value systems in India. Some reasons for this are obvious, like knowledge of English and India’s cut-throat educational system. But there are some other non-obvious ones, and here are five reasons why I believe India (and Indian traffic) has moulded so many Indian CEOs:

Humility: Rajghatta writes about how Satya Nadella’s very first email to employees after he became CEO of Microsoft started with “Today is a very humbling day for me”. His personal family situation taught him humility; so did an Indian upbringing. Humility leads to loyalty, with most Indians brought up to think of a job for life and one’s company as a respected second family. It fosters consensus building and collaboration, and you do not think of yourself as an alpha leader, which is a very common Western CEO trait.

Gentleness and family: Entrepreneur Vivek Wadhwa once told the BBC (bbc.in/3VjFdrZ) that “men like Nadella and Sundar Pichai bring a certain amount of caution, reflection and a gentler culture” that makes them ideal candidates for tech top jobs in tech, especially at this juncture when Big Tech has to answer a lot of questions from governments and society. Joint families, parents invested in education and growing up in an unequal society tend to instil tolerance and kindness.

Having a Plan B: “No other nation in the world ‘trains’ so many citizens in such a gladiatorial manner as India does,” writes R. Gopalakrishnan of Tata Sons. There is always a Plan B, “in case there is suddenly no electricity, or the water runs out”. Things never worked smoothly in India and rarely followed a logical process, so one is always prepared. In times when uncertain events like covid or global warming are hitting us, these inborn skills matter greatly.

The concept of time: In Indian mythology, time is circular, not linear. There are no binaries, we live in shades of grey. Thus, work supersedes leisure, there is no work-life sequence, and both need to be integrated. The past is not gone, it may return. These uncertain times, with tech evolving at blinding speed and work changing forever, favour such thinking among corporate leaders.

Finally, unity in diversity: Indians grew up with 22 official languages, scores of religions, countless castes and subcastes. In a work culture embracing diversity, this background is useful. Indians have grown up in a democratic society with independent institutions and a free press, in a society “which strives to be equitable albeit with deep inequities”.

As the world increasingly begins to reflect the traffic in India—typically unpredictable, complex and chaotic—growing up with it gives the planet’s Nadellas, Pichais and Agarwals an almost unfair advantage to rule the world of Big Tech.