Five Things The Tech Sector Crash Got Right in India

Jaspreet Bindra

Much has been written about the tech crash of 2022, with companies from Zoom, Netflix and even the giants like Amazon and Meta losing hundreds of billions of dollars value over the past few months. Most of it is about hyped-up expectations, back-room shenanigans, and crypto scams and many are speculating that the luster of tech growth stocks is dimming. It was refreshing, therefore, to find John Thornbill display a rare ray of optimism in his Financial Times article, ‘The five things the tech bubble got right’. He draws inspiration from a 2004 post-dotcom crash essay by tech guru Paul Graham, ‘What The Bubble got Right’, in which Graham posits that “stock market investors were right about the direction of travel even if they were wrong about the speed of the journey.” Thornbill’s first point in his list of five is how we learnt to attach value to data, with data rich companies being valued disproportionately high.Second, he says, while globalization seems to be receding, the world is ‘e-globalizing’ with 63% of the world connected to the internet, enabling information, reach and talent at a global scale. Third is that the world of work has irrevocably changed for the better – with hybrid work, the mass resignation, and the rise of ‘liquid’ companies. Fourth in his list is the massive energy transition from fossil fuels to electric, led by Tesla. And, finally, while crypto has crashed, the enthusiasts are asking the right questions around decentralization and democratization of the Internet.

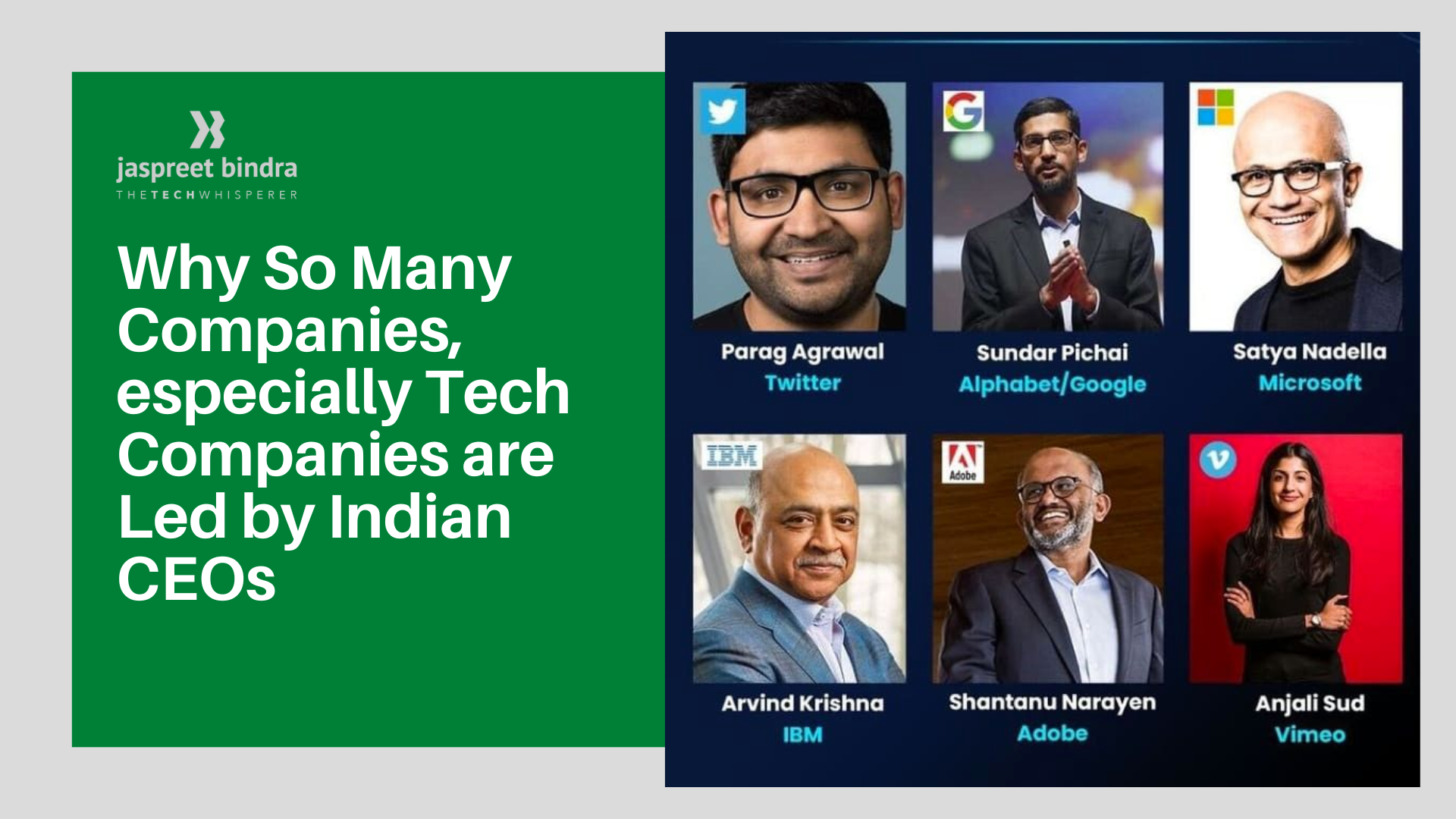

The tech crash has played out in India too, especially hitting the unicorns hard. Byjus, the world’s largest edtech unicorn, seems to be tottering, the Paytm and Zomato have destroyed several billion dollars of wealth in the local market. Funding seems to have dried up, unicorns are scrambling for down rounds, and larger tech companies are tightening their belts. In this tech gloom, I started wondering on what are the five things that the tech cash got right in India; what were the things in common with Thornbill’s global five, and what was different. In my view, the market valued data rich companies very similarly to the rest of the world, explaining the enormous IPO valuations of loss-making but data-rich giants like Paytm and Zomato. However, in India, this value of data was taken a step further towards societal value. Nandan Nilekani talked about how the creation and flow of personal and public data from Indian citizens could make Indians ‘data rich, before they became economically rich’, thus paving the way for monetizing data for the creator, through data fiduciaries, rather than for an intermediary platform. This brings me to my second point, where the enormous public digital infrastructure like Aadhar and UPI, led again by Nilekani, has e-united India. This India Stack is now getting richer, with digital health records and the Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC). Jio and other telcos are racing to connect every Indian to these services, and even if our country be divided by politics or language, it is united by digital. Thirdly, technology and COVID have brought the future of work to the present in India too. While there are no Great Resignations, hybrid work is de rigueur, and the workforce are increasingly getting decentralized. This, I believe, is particularly good for the country as Tier 3 and 4 cities open up for talent and work-from- home gives more opportunities to women. The fact that work has irrevocably changed here too is evidenced by the backlash against moonlighting by Wipro and other IT companies. (My strong belief is that moonlighting is inevitable, but more on that in a later column).Fourth, there is a transition to electric too, but in a uniquely Indian manner – it is the two and three wheeler that are leading the charge, accounting for more than 90% of total EV sold. Lastly, a trend which is not necessarily Indian but is rooted in India, is how even as tech stocks sank, Indian CEOs rose to the top of global tech companies. Much has been written about this,and my belief is that the turbulence of the pandemic has brought out the needs for skills, values and coping mechanisms that are uniquely Indian (again, I will reserve the details for a later column). It could be argued that all of these ‘Indian’ CEOs are US citizens. However, it is interesting to note that most of them are first generation, and they absorbed their early values and customs in this country. Even as the world reels in shock from the crash, the war, and the downturn, I hope that these positives and these leaders lead us back into the light.