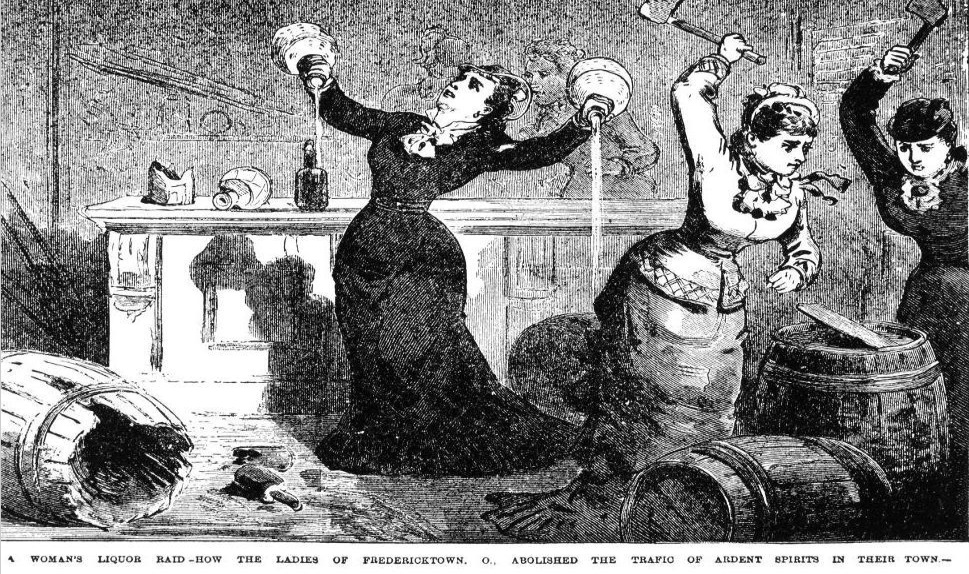

The new Temperance Movement that businesses should embrace

Jaspreet Bindra

Over the 18th and 19th centuries, Britain and the New World countries were awash with alcohol, a beverage as widespread as coffee or tea is today. Children were given beer for breakfast, Gin was famously the ‘Mother’s Ruin’ in England inebriating millions of women and men, and Native Americans used to trade alcohol against fur. As the social and medical ill effects of alcohol came to light, a strong movement towards total abstinence was born; it was called the Temperance Movement. Seizing the opportunity this movement afforded, Thomas Cook, a Market Harborough started a fledgling travel company which organized railway outings for members of the local Temperance Movement.

Over 178 years, the company expanded into air travel, hotel bookings, started running its own excursions, and buying and operating its own planes, hotels and cruise ships, giving travelers and end-to-end Thomas Cook experience and becoming the largest travel company in the UK. It became a huge global travel group, with annual sales of £9bn, 19 million customers a year and 22,000 people offering travel services in 16 countries. However, all the years of work unraveled in perhaps a month – Thomas Cook suddenly ceased operations leaving millions of travelers and thousands of employees stranded all over the world. Many reasons have been given for this spectacular fall from grace – a $2bn debt pile, botched acquisitions, the Turkey political situation, even the 2018 heat wave in Europe.

But perhaps the most insidious reason has been structural – the business model of travel has fundamentally changed. A business model can be defined as ‘how your company creates, delivers and captures value’. Traditionally business models have been linear, with investment and raw material at one end, and revenue and customer at the other – what the business guru Sangeet Paul Choudary famously calls ‘pipe models’. These models are rapidly changing to ‘platform business models’, where there is “cost and revenue at both ends” – think Uber or YouTube or Airbnb. Here, you do not produce stuff for people to own, but most often customers rent the stuff you make, or, more often, rent stuff which already exists. There are four big reasons platform models are taking over the world:

- The age of the millennials: This fast-emerging customer segment would rather rent things than own them, they do not equate status with ownership. They would rent a house, Uber to work, rent furniture, rent a Gucci dress for a party

- Experiences matter: What they would pay for, however, is experiences. Thus, they would spend money on travel or eating out or on skydiving over Machhu Picchu, rather than buy a house or a car. However, they want to choose how and when they do so and want to be in control of it.

- Caring for the environment: is very important. People are turning against the concept of producing new cars or houses, there are enough in surplus that already exist, and these can be rented out

- Finally, there is technology: The advent of mobile networks, smartphones, mapping platforms, big data and analytics, algorithms and artificial intelligence have enabled tech companies to quickly and efficiently match demand and supply, and ‘dematerialise’ a physical object such as a hotel or a car and bring it to the phone screen. Atoms are rapidly turning into bits

Thus, customers do not want to consume holidays the way they did, they, they would rather decide and plan a holiday on the fly: renting someone’s beach house, booking a ticket, and take a car on demand, using technology and information that they have in their hand. Holidays are no longer a set-menu, experience where one operator controls all or large parts of it, but a large, infinite buffet of experiences that technology enables a customer to choose quickly and cheaply from.

This is what perhaps Thomas Cook missed or did not react fast enough to embrace – the structural change of travel itself, catalyzed by a new kind of customer and a set of data-driven technologies. It is not that they did not see the world changing around them, but as author Pam Henderson says, “Just as a fish doesn’t know it is wet, so companies often can’t see or feel the very opportunities where they are swimming.”

I believe that many sectors of the economy are in similar waters. Take the auto sector for example: if I were an auto executive, I would be looking very closely at Thomas Cook. The same trends are simmering – customers are less likely to own cars; they would rather rent one and technology companies like Uber and Ola have almost overnight emerged to fulfil that need. The advent of electric and autonomous is only going to fuel this trend further. The current auto downturn in India is driven by many factors, much like the collapse of Thomas Cook was – bad economy, cyclical overcapacity, global uncertainty. But the insidious and powerful monster lurking below the surface is the monumental structural business model change, cooked up by technology and changing customer preferences.

I believe that auto makers need to look at this crisis as something ‘too good to waste’, an opportunity to start effecting change in their very industry structure. Some of them have already started doing so – cars are now available on subscription, many are being made tailored for fleets, customer experience is going beyond the showroom. However, the change needs to be faster and more radical if they intend to survive and grow, and not end up like the travel company that Thomas Cook started. The auto industry has been intoxicated on demand and growth for many decades now; in some sense, it is now their Temperance Movement.

(Note: Thomas Cook India is separate from Thomas Cook globally, with a different ownership and management, and has been completely unaffected by the global collapse)