A creature rises from the dead to challenge the virtual world

Jaspreet Bindra

About a month back, a Mastodon raised its woolly head in India and trumpeted its unexpected appearance with a volley of ‘toots’. The sudden emergence of a species thought to be extinct was aided by a Supreme Court lawyer, Sanjay Hegde. Thousands of followers of the existing colossus started migrating to this new challenger, significantly boosting its numbers and heralding its arrival.

Before you start scratching your own woolly head in bewilderment, let me explain: Mastodon is a new social network which looks, feels and acts like Twitter, but is not Twitter. It is a new kind of social network, one which is decentralised. It looks exactly like Twitter does, but tweets are called toots, retweets are called boosts, a like is a favourite, 140 characters give way to 500, and there are a profusion of privacy settings which allow you to control the content, as well as its distribution.

So, what is the big deal, you might ask? A plethora of social networks have come, raised their heads and have been clubbed down, including from leviathans like Google and Microsoft. Some of those, TikTok being a notable example have stayed on and prospered, but these are the very rare diamonds in the rough. So, is this another passing fad, which raises its head for a brief moment in history before being hunted into irrelevance and extinction?

Well, Mastodon is different: it is ‘federated. unlike a highly centralized and controlled Twitter or a Facebook. In Mastodon, you do not log on to one monolithic, centralized service but actually log into a specific ‘instance’ – so it is a network of connected nodes, and the instances are the specific nodes your account lives in. Mastodon developer Eugen Rochko explained this federated concept in a Medium post, comparing it to email and Star Trek: “… users are spread throughout different, independent communities, yet remain unified in their ability to interact with each other. You can send an Outlook email user a message from your Gmail account, even though you’re not using the same service — Mastodon works the same way. So, it isn’t just a website, it is a federation—think Star Trek. Thousands of independent communities running Mastodon form a coherent network, where while every planet is different, being part of one is being part of the whole.”

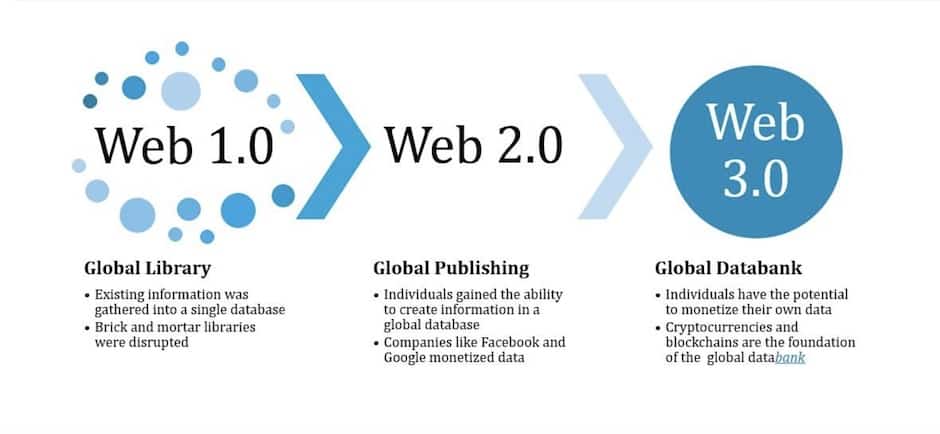

“Mastodon has no money, no advertisements, no venture capital—and doesn’t plan on getting any. It has no board of directors, no VP of product, no Chief Financial Officer. Peter Thiel will never partly own Mastodon.”, writes Sarah Leong in Vice. And, this is actually the big deal. Mastodon is perhaps the first popular consumer application of what is called the Decentralised Web, or the DWeb. The DWeb was born in late 2018 in the Decentralised Web Summit in San Francisco, hosted by the Internet Archive. First the backstory: The World Wide Web was envisaged as a peer-to-peer network of computers where you connected and talked directly with your friends. But soon we started talking through the massive, centralized services provided by Google, Facebook, Microsoft and Amazon, and pure P2P started fading away. We started living in the ‘walled gardens’ created by them, and all our data, information and services started living in their massive clouds. “Our laptops have become just screens. They cannot do anything useful without the cloud,” says Muneeb Ali of Blockstack, a platform for building decentralised apps. The DWeb is about going back to the roots, back to decentralizing things, so that we keep control our data and interact directly with others in our network.

But, why, you might ask is that necessary, when these companies provide you excellent services free? Well, there is nothing free on the Internet, if it is free, then you are the product! The large companies sell you to advertisers, as sliced and diced packets of your intimate data. Also, if something is centralized it can very easily be controlled by the corporations or the government – witness China, or the recent shutdown in Iran, or the blacklisting of Sanjay Hegde by Twitter which brought the Mastodon out of the Ice Age. The DWeb is built differently – “your computer not only requests services but provides them too”, writes Zoe Corbyn, in an excellent piece in The Guardian, and “DWeb protocols do not use http, but use protocols which identify information based on what it is, rather than where it is”. All this data is stored across millions of decentralised computers or servers, making single point control and access impossible”.

One of the core technologies behind the DWeb is Blockchain – it’s very decentralizing nature and currency support make it ideal for the DWeb. Filecoin is an excellent example of decentralised storage, where you can store others’ data in the spare capacity of your computer, and earn Filecoins in exchange, with all such deals getting immutably and securely recorded on a blockchain. Many more such DApps (or Distributed Apps) will get created. 1Ramp in India is creating a next gen distributed social network for artists, DTube is a decentralised YouTube, DMail is, predictably, distributed Email. The distributed web is still being built, and it will have its own problems. While centralization prevents censorship, it also prevents control by the good guys, and privacy laws would get even tougher to implement. It is more difficult to engineer than the centralized web, and the ‘network effects’ of all your friends being there, so that you have to, will take forever to happen.

However, I believe that it is an inevitability. Our world is getting increasingly centralized, not only in technology, but also socially, economically, and geographically. The backlash against this concentration of power, money and data in the hands of the very few has started gaining momentum. This desire for an equitable distribution will shape politics, society, countries and the Web. Mastodons were solitary creatures, and fossil evidence indicates that mastodons probably disappeared from earth about 10000 years ago as a part of a mass extinction, probably due to human hunting pressure. Time for them to come back.

(This was published as a column in Mint, dated 28 Nov 2019)